This article was originally published on The Secular Heretic on February 16, 2022.

Why is it considered “settled science” among epidemiologists, virologists and the general public that certain diseases like Influenza and COVID-19 are transmitted through human contact, when in fact it has never been proven that diseases spread this way? For more than a century Germ Theory has had the dominance and authority of religious orthodoxy, yet a far more plausible explanation for how and why we get “infected” with certain illnesses is Terrain Theory, which illustrates that a multitude of environmental and genetic components combine to determine the incidence of disease in a population or individual. In the following essay, Torsten Engelbrecht, Dr. Claus Köhnlein, MD and Dr. Samantha Bailey, MD draw on material gathered in their extraordinary book Virus Mania to reveal the explanatory power of terrain theory.

For about 120 years in particular, people have been very susceptible to the idea that certain microbes act like predators, stalking our communities for victims and causing the most serious illnesses named COVID-19, AIDS, hepatitis C, avian flu etc. But such an idea is thoroughly simple, too simple. Unfortunately, as psychology and social science have discovered, humans have a propensity for simplistic solutions, particularly in a world that seems to be growing increasingly complicated. But medical and biological realities, like social ones, are just not that simple. Renowned immunology and biology professor Edward Golub’s rule of thumb is that, “if you can fit the solution to a complex problem on a bumper sticker, it is wrong! I tried to condense my book The Limits of Medicine: How Science Shapes Our Hope for the Cure to fit onto a bumper sticker and couldn’t.” [1]

By focusing on microbes and accusing them of being the primary and lone triggers of disease, we overlook how various factors causing illness are linked together, such as environmental toxins, the side effects of medications, psychological issues like depression and anxiety, and poor nutrition. If over a longer period of time, for instance, you eat far too little fresh fruits and vegetables, and instead consume far too much fast food, sweets, coffee, soft drinks, or alcohol (and along with them, all sorts of toxins such as pesticides or preservatives), and maybe smoke a lot or even take drugs like cocaine or heroin, your health will eventually be ruined. Drug-addicted and malnourished junkies aren’t the only members of society who make this point clear to us.

For billions of years, nature has functioned as a whole with unsurpassed precision. Microbes, just like humans, are a part of this cosmological and ecological system. If humanity wants to live in harmony with technology and nature, we must be committed to understanding the supporting evolutionary principles ever better and to applying them properly to our own lives. Whenever we don’t do this, we create ostensibly insolvable environmental and health-related problems.

“The doctor should never forget to interpret the patient as a whole being.”

Dr. Rudolf Virchow

These are thoughts which Rudolf Virchow (1821-1902), a well-known doctor from Berlin, had when he required in 1875 that “the doctor should never forget to interpret the patient as a whole being.”[2] The doctor will hardly understand the patient, then, if he or she does not see that person in the context of a larger environment. Without the appearance of bacteria, human life would be inconceivable, as bacteria were right at the beginning of the development towards human life.

Bacteria could very well exist without humans; humans, however, could not live without bacteria! It is, therefore, unreasonable to conclude that these mini-creatures, whose life-purpose and task throughout biological history has been to build up life, are, in fact, the greatest, singular causes of disease and death. Yet, the prevailing allopathic medical dogma of one disease, one cause, one miracle pill has dominated our thinking since the late 19th century, when Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch became heroes.

Prior to that, we had a very different mindset, and even today, there are still traces everywhere of this different consciousness. “Since the time of the ancient Greeks, people did not ‘catch’ a disease, they slipped into it. To catch something meant that there was something to catch, and until the germ theory of disease became accepted, there was nothing to catch,” writes Edward Golub in his work. Hippocrates, who is said to have lived around 400 B.C., and Galen (one of the most significant physicians of his day; born in 130 A.D.), represented the view that an individual was, for the most part, in the driver’s seat in terms of maintaining health with appropriate behavior and lifestyle choices. “Most disease [according to ancient philosophy] was due to deviation from a good life,” says Golub. “[And when diseases occur] they could most often be set aright by changes in diet—[which] shows dramatically how 1,500 years after Hippocrates and 950 years after Galen, the concepts of health and disease, and the medicines of Europe, had not changed”[3] far into the 19th century. The German Max von Pettenkofer (1818-1901), once appointed rector of the University of Munich, jeered: “Bacteriologists are people who don’t look further than their steam boilers, incubators and microscopes.”[4]

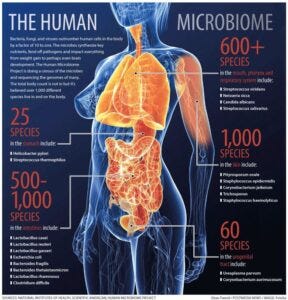

Just a few hours after birth, all of a newborn baby’s mucous membrane has already been colonized by bacteria, which perform important protective functions. Without these colonies of billions of germs, the infant, just like the adult, could not survive. What’s more, only a small part of our body’s bacteria have been discovered.[5] “The majority of cells in the human body are anything but human: foreign bacteria have long had the upper hand,” reported a research team from Imperial College in London under the leadership of Jeremy Nicholson in the journal Nature Biotechnology in 2004.[6] In the human digestive tract alone, researchers came upon around 100 trillion microorganisms, which together have a weight of up to one kilogram. “This means that the 1,000-plus known species of symbionts probably contain more than 100 times as many genes as exist in the host,” as Nicholson states. It makes you wonder how much of the human body is “human” and how much is “foreign.”

Nicholson calls us “human super-organisms”—as our own ecosystems are ruled by microorganisms. “It is widely accepted,” writes the Professor of Biochemistry, “that most major disease classes have significant environmental and genetic components and that the incidence of disease in a population or individual is a complex product of the conditional probabilities of certain gene components interacting with a diverse range of environmental triggers.”[7] Above all, nutrition has a significant influence on many diseases, in that it modulates complex communication between the 100 trillion microorganisms in the intestines!

“Alone the production of a large part of the food that lands on our plates is dependent on bacterial activity.”

Dr. René Dubos

How easily this bacterial balance can be decisively influenced can be seen with babies: If they are nursed with mother’s milk, their intestinal flora almost exclusively contains a certain bacterium (Lactobacillus bifidus), which is very different from the bacterium most prevalent when they are fed a diet including cow’s milk. “The bacterium lactobacillus bifidus lends the breast-fed child a much stronger resistance to intestinal infections,” writes microbiologist René Dubos. This is just one of countless examples of the positive interaction between bacteria and humans. “But unfortunately, the knowledge that microorganisms can also do a lot of good for humans never enjoyed much popularity.” As Dubos points out:

Humanity has made it a rule to take better care of the dangers that threaten life than to take interest in the biological powers upon which human existence is so decisively dependent. The history of war has always fascinated people more than descriptions of peaceful coexistence. And so it comes that no one has ever created a successful story out of the useful role that bacteria play in stomach and intestines. Alone the production of a large part of the food that lands on our plates is dependent on bacterial activity.[8]

In this context, it should not be forgotten that a gigantic industry has been built up around the fear of microbes, earning multi-billion dollar profits from the sale of drugs and vaccines, whereas no one earns nearly as much money from advising folk to eat healthier, exercise more, breathe more fresh and clean air, or do more for one’s emotional well-being.

One may ask, But haven’t antibiotics helped or saved the lives of many people? Without a doubt. But, we must note that it was only as recently as 12 February 1941, that the first patient was treated with an antibiotic, specifically penicillin. Therefore, antibiotics have nothing to do with the increase in life expectancy, which really took hold in the middle of the 19th century (in industrialized countries), almost a century before the development of antibiotics; and plenty of substances—including innumerable bacteria essential to life—are destroyed through the administration of antibiotics, which directly translated from the Greek, means, “against life.” Further, nowadays millions of antibiotics are unnecessarily administered, and in fact antibiotics are held responsible for nearly one fifth of the more than 100,000 annual deaths that are traced back to medication side effects in the United States alone.

Indeed, the ledger for vaccinations of any kind reads poorly because there is no solid, placebo-controlled study demonstrating that vaccination—usually an intervention on a healthy body—is better than doing nothing. Meanwhile, there are placebo-controlled studies showing that vaccination is worse than doing nothing—as well as dozens of studies showing that the unvaccinated are better off than the vaccinated.[9]

Furthermore, “It is well known that deaths from common infectious diseases declined dramatically before the advent of most vaccines due to improved environmental conditions—even diseases for which there were no vaccines,” as Anthony R. Mawson, professor of epidemiology and biostatistics, pointed out in 2018.[10] This is exemplified by measles. The measles vaccination was introduced in West Germany in the mid-1970s (see the syringe in the graphic below), at a time when the “measles scare” was essentially over.

If we ask bacteriologists which comes first: the terrain or the bacteria, the answer is always that it is the environment (the terrain) that allows the microbes to thrive. The germs, then, do not directly produce the disease. So, it is evident that the crisis produced by the body causes the bacteria to multiply by creating the proper conditions for actually harmless bacteria to become poisonous, pus-producing microorganisms. This explains why the dominant medical thought pattern can’t comprehend that so many different microorganisms can co-exist in our bodies (among them such “highly dangerous” ones as the tuberculosis bacillus, the Streptococcus or the Staphylococcus bacterium) without bringing about any recognizable damage. They only become harmful when they have enough of the right kind of food. Depending on the type of bacterium, this food could be toxins, metabolic end products, improperly digested food and much more.

Pasteur finally became aware of all of this, quoting Bernard’s dictum —“the microbe is nothing, the terrain is everything”—on his deathbed. But Paul Ehrlich (1854-1915), known as the father of chemotherapy, adhered to the interpretation that Robert Koch preached: i.e. that microbes were the actual causes of disease. For this reason, Ehrlich, who his competitors called “Dr. Fantasy,“ dreamed of “chemically aiming” at bacteria, and decisively contributed to helping the “magic bullets” doctrine become accepted, by treating very specific illnesses successfully with very specific chemo-pharmaceutical preparations. This doctrine was a gold rush for the rising pharmaceutical industry with their wonder-pill production. “But the promise of the magic bullet has never been fulfilled,” writes Allan Brandt, a medical historian at Harvard Medical School.[11]

Viruses measure only 20-450 nanometers (billionths of a meter) . . . so tiny, that one can only see them under an electron microscope.

This distorted understanding of bacteria and fungi and their functions in abnormal processes shaped attitudes toward viruses. At the end of the 19th century, as microbe theory rose to become the definitive medical teaching, no one could actually detect viruses, which measure only 20-450 nanometers (billionths of a meter) across and are thus very much smaller than bacteria or fungi—so tiny, that one can only see them under an electron microscope. And the first electron microscope was not built until 1931. Bacteria and fungi, in contrast, can be observed through a simple light microscope.

“Pasteurians” were already using the expression “virus” in the 19th century, but this is ascribed to the Latin term “virus” (which just means poison) to describe organic structures that could not be classified as bacteria. It was a perfect fit with the concept of the enemy: if no bacteria can be found, then some other single cause must be responsible for the disease. Readers may wonder how it can be continually claimed that this or that virus exists and has potential to trigger diseases through contagion. An important aspect in this context is that some time ago, mainstream virus-science left the road of direct observation of nature, and decided instead to go with so-called indirect “proof” with procedures such as antibody and PCR tests, despite the fact that these methods lead to results which have little to no meaning.

A virus with indeterminate characteristics cannot be proven by PCR any more than it can be determined by a little antibody test. And even if scientists assume that the genetic sequences discovered in the laboratory belong to the viruses mentioned, this is a long way from proving that the viruses are the causes of the diseases in question, particularly when the patients or animals that have been tested are not even sick, which often enough is the case.

Another important question must be raised: even when a supposed virus does kill cells in the test-tube (in vitro), or results in embryos in a chicken egg culture dying, we cannot safely conclude that these findings can be carried over to a complete living organism (in vivo)! For example, the particles termed viruses stem from cell cultures (in vitro) whose particles could be genetically degenerate because they have been bombarded with chemical additives like growth factors or strongly oxidizing substances. These effects were demonstrated with antibiotic use in a 2017 study.[12]

In 1995, the German news magazine Der Spiegel delved into this problem (something that is worth noting, when one considers that this news magazine usually runs only orthodox virus coverage), quoting researcher Martin Markowitz from the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center in New York:

The scientist [Markovitz] mauls his virus-infected cell cultures with these poisons in all conceivable combinations to test which of them kill the virus off most effectively. “Of course, we don’t know how far these cross-checks in a test-tube will bring us,” says Markowitz. “What ultimately counts is the patient.” His clinical experience has taught him the difference between test-tube and sick bed.[13]

“Unfortunately, the decade is characterized by climbing death rates, caused by lung cancer, heart disease, traffic accidents and the indirect consequences of alcoholism and drug addiction,” wrote Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet, recipient of the Nobel Prize for Medicine, in his 1971 book Genes, Dreams, and Realities. “The real challenge of the present day is to find remedies for these diseases of civilization. But nothing that comes out of the labs seems to be significant in this context; laboratory research’s contribution has practically come to an end. For someone who is well on the way to a career as a lab researcher in infectious disease and immunology, these are not comforting words.”[14]

To biomedical scientists and the readers of their papers, Burnet continued, it may be exciting to hold forth on “the detail of a chemical structure from a phage’s [viruses from simple organisms; see below] RNA, or the production of antibody tests, which are typical of today’s biological research. But modern fundamental research in medicine hardly has a direct significance to the prevention of disease or the improvement of medical precautions.”[15]

Medical teaching is entrenched in Pasteur and Koch’s reality-distorting focus on one enemy, and has neglected also to pursue the thought that the body’s cells could produce a virus on its own accord, for instance as a reaction to stress factors. The experts discovered this a long time ago, and speak of “endogenous viruses”—particles that form inside the body’s cells themselves.

In this context, the research work of geneticist Barbara McClintock is a milestone. In her Nobel Prize paper from 1983, she reports that the genetic material of living beings can constantly alter, by being hit by “shocks.”[16] These shocks can be toxins, but can also be from other materials that produced stress in the test-tube. This in turn can lead to the formation of new genetic sequences, which were unverifiable (in vivo and in vitro) before.

Torsten Engelbrecht works as an investigative journalist in Hamburg and is an author of the heretical and still unchallenged book Virus Mania (co-authored by Dr. Claus Köhnlein, MD, Dr. Samantha Bailey, MD, and Dr. Stefano Scoglio, BSc). In 2009, he received the Alternative Media Award for his article “The Amalgam Controversy.” He was trained at the renowned magazine for professional journalists Message and was a full-time editor at the Financial Times Deutschland, among others. As a freelance journalist, he has written articles for publications such as OffGuardian, The Ecologist, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, Rubikon, Freitag, Geo Saison, and Greenpeace Magazine. In 2010, his book Die Zukunft der Krebsmedizin (The Future of Cancer Medicine) was published, with Dr. Claus Köhnlein, MD, and two other doctors as co-authors. For more details see www.torstenengelbrecht.com.

Dr. Claus Köhnlein, MD, is a medical specialist of internal diseases. He completed his residency in the Oncology Department at the University of Kiel. Since 1993, he has worked in his own medical practice, treating both Hepatitis C and AIDS patients who are skeptical of antiviral medications. Köhnlein is one of the world’s most experienced experts when it comes to alleged viral epidemics. In April 2020, he was mentioned in the OffGuardian article “8 MORE Experts Questioning the Coronavirus Panic.” An interview with him by Russia Today editor Margarita Bityutskikh, published on Youtube in September 2020 on the topic of “fatal COVID-19 over-therapy,” garnered 1.4 million views within a short time.

Dr. Samantha Bailey, MD, is a research physician in New Zealand. She completed her Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery degree at Otago University in 2005. She has worked in general practice, telehealth and in clinical trials for over 12 years with a particular interest in novel tests and treatments for medical diseases. She has the largest Youtube health channel in New Zealand, and creates educational health videos based on questions from her audience. For her full, uncensored repertoire, visit her website.

Footnotes

- Golub, Edward. The Limits of Medicine: How Science Shapes Our Hope for the Cure. The University of Chicago Press, 1997: xiii.

- Langbein, Kurt and Bert Ehgartner. Das Medizinkartell: Die sieben Todsünden der Gesundheitsindustrie. Piper, 2003: 37.

- Golub, Edward. The Limits of Medicine: How Science Shapes Our Hope for the Cure. The University of Chicago Press, 1997: 37-40.

- Langbein, Kurt and Bert Ehgartner. Das Medizinkartell: Die sieben Todsünden der Gesundheitsindustrie. Piper, 2003: 51.

- Blech, Jörg. Leben auf dem Menschen: die Gesundheitserreger. S. Fischer Verlage. Frankfurt am Main, 2014. (see www.aegis.at)

- Nicholson, Jeremy K., Elaine Holmes, John C. Lindon, and Ian D. Wilson. “The challenges of modeling mammalian biocomplexity.” Nature Biotechnology, 22. 2004: 1268-1274. (see https://www.nature.com/articles/nbt1015)

- Nicholson, Jeremy K., Elaine Holmes, John C. Lindon, and Ian D. Wilson. “The challenges of modeling mammalian biocomplexity.” Nature Biotechnology, 22. 2004: 1268-1274. (see https://www.nature.com/articles/nbt1015)

- Dubos, René. Mirage of Health: Utopias, Progress, and Biological Change. Harper & Brothers, 1959: 69.

- Engelbrecht, Torsten, Claus Köhnlein, Samantha Bailey, Stefano Scoglio. Virus Mania: Corona/COVID-19, Measles, Swine Flu, Cervical Cancer, Avian Flu, SARS, BSE, Hepatitis C, AIDS, Polio, Spanish Flu: How the Medical Industry Continually Invents Epidemics, Making Billion-Dollar Profits at Our Expense, 3rd English Edition. Books on Demand, 2021: 348-357.

- Mawson, Anthony R.. “Vaccination and Health Outcomes,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Special Issue, July 15, 2018. (see https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph/special_issues/vaccination?view=compact&listby=date)

- Brandt, Allan. No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States Since 1880. Oxford University Press, 1985: 161.

- Buzás, Edit I. et al. “Antibiotic-induced release of small extracellular vesicles (exosomes) with surface-associated DNA.” Scientific Reports, 15 August 2017.

- Grolle, Johann. “Siege, aber kein Sieg.” Der Spiegel, 29, 1995.

- Burnet, Sir Frank Macfarlane. Genes, Dreams and Realities. Medical and Technical Publishing, 1971: 217-218.

- Burnet, Sir Frank Macfarlane. Genes, Dreams and Realities. Medical and Technical Publishing, 1971: 217-218.

- McClintock, Barbara. “The Significance of Responses of the Genome to Challenge.” Nobel speech, 8 December 1983.

Dr. Samantha Bailey

Sam is a content creator, medical author & health educator.

- Dr. Samantha Baileyhttps://drsambailey.com/author/sam/

- Dr. Samantha Baileyhttps://drsambailey.com/author/sam/

- Dr. Samantha Baileyhttps://drsambailey.com/author/sam/

- Dr. Samantha Baileyhttps://drsambailey.com/author/sam/